Keynesian versus Monetarist Economic Thought: A Comparative Analysis

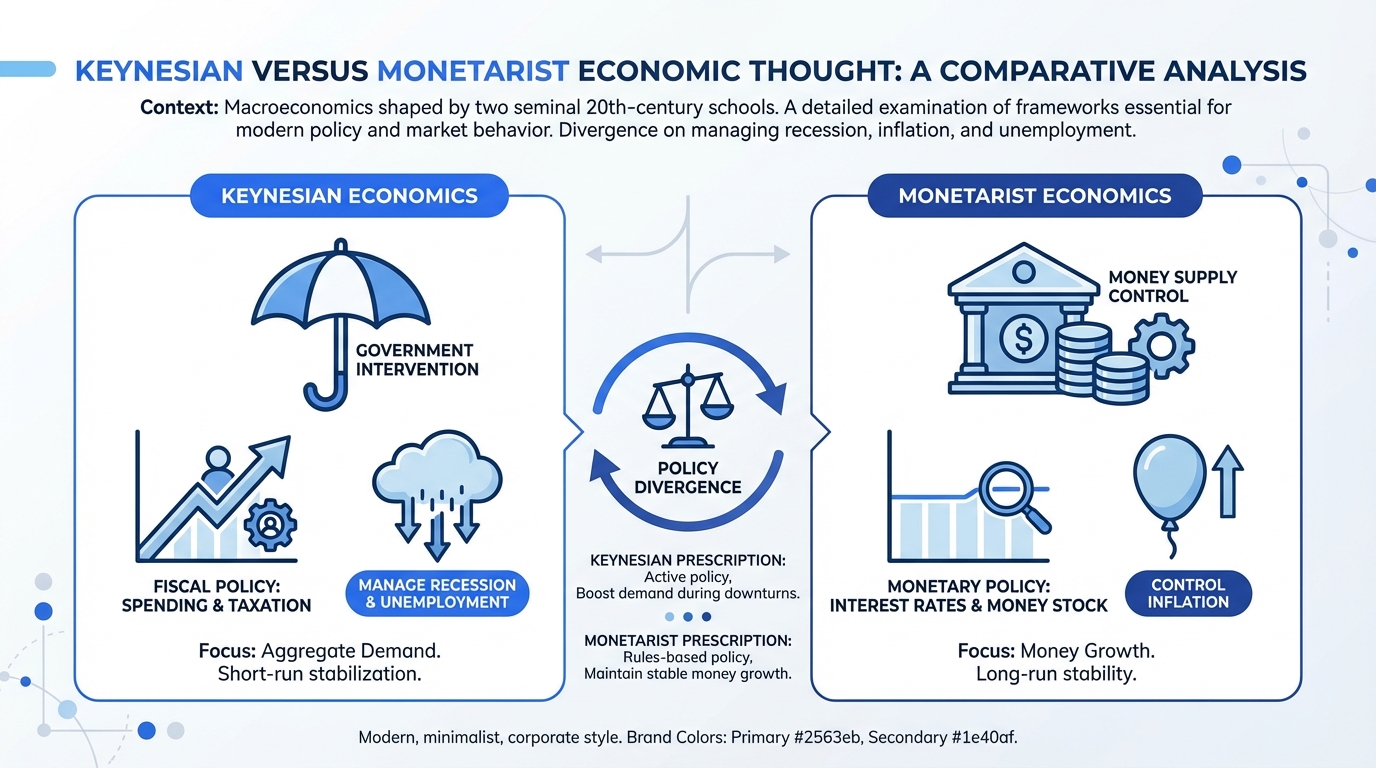

Macroeconomics is mainly influenced by two key theories from the 20th century: Keynesian economics and Monetarism. This analysis offers a detailed comparison of these frameworks, crucial for understanding current economic policy and market behavior.

These theories offer vastly different prescriptions for managing the economy, particularly concerning issues of recession, inflation, and unemployment. Their divergence centers on the inherent stability of private markets and the appropriate role of government intervention.

Understanding these principles is essential for both studying Economics and making real-world financial decisions. Policy changes influenced by these models greatly impact personal finance strategies and investments in stocks, bonds, and ETFs.

Foundational Divergence: Market Stability and Government Role

Keynesian economics, rooted in the work of John Maynard Keynes, emerged during the Great Depression. This school posits that capitalist economies are inherently unstable and prone to long periods of depressed demand and high unemployment.

Keynesians believe that prices and wages are “sticky,” meaning they don’t adjust quickly enough to maintain full employment. Therefore, the economy requires active, discretionary fiscal intervention by the government to manage aggregate demand.

In contrast, Monetarism, popularized by Milton Friedman and the Chicago School, views the private sector as inherently stable and self-correcting. Monetarists argue that economic instability, recessions, and inflation are primarily caused by erratic government intervention, particularly misguided monetary policy.

Monetarists support the natural rate hypothesis, arguing that the economy will eventually stabilize at a consistent level of output and employment, regardless of short-term fiscal stimulus.

Intellectual Foundations and Core Principles

The theoretical bedrock of Keynesian thought is the principle of effective demand and the income-expenditure model. Keynes highlighted the multiplier effect, where a change in government spending or investment results in a larger change in national income.

Keynes’s The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money (1936) fundamentally challenged classical ideas about automatic self-correction and flexible markets.

Monetarism is grounded in the Quantity Theory of Money (QTM), summarized by the equation MV = PY (Money Supply × Velocity = Price Level × Real Output). Monetarists assert that the velocity of money (V) is stable and predictable in the long run.

This stability implies a direct, causal link: changes in the money supply (M) directly and proportionally influence nominal GDP (PY). Friedman and Anna Schwartz’s *A Monetary History of the United States* strongly supports the view that “inflation is always and everywhere a monetary phenomenon.”

Contrasting Core Mechanisms

The two schools differ profoundly on the flexibility of economic variables and the causes of economic distress. These differences drive their respective policy recommendations.

Price and Wage Flexibility

-

- Keynesian View: Wages and prices are sticky, especially downward. This rigidity prevents markets from clearing quickly during a recession, necessitating external stimulus to boost demand.

- Monetarist View: Markets are highly flexible, especially in the long run. Short-term stickiness is usually linked to government regulations or minimum wage laws, but long-term results are determined by market forces.

Causes of Recessions

-

- Keynesian View: Recessions stem from insufficient aggregate demand (a shortfall in spending, investment, or consumption). This can be caused by pessimism, liquidity traps, or sudden drops in investment confidence.

- Monetarist View: Recessions are primarily caused by sharp contractions in the money supply or instability introduced by the central bank. The Great Depression, for instance, is viewed as a failure of the Federal Reserve to maintain adequate liquidity.

The Role of Interest Rates

Keynesians view interest rates as having a limited effect on investment during deep recessions, especially if expectations are poor. Monetarists believe that interest rates are key in how changes in the money supply impact real economic activity and inflation expectations, affecting market news.

These differences result in varying policy recommendations, especially in how governments and central banks utilize fiscal and monetary tools to manage the economy and maintain financial stability.

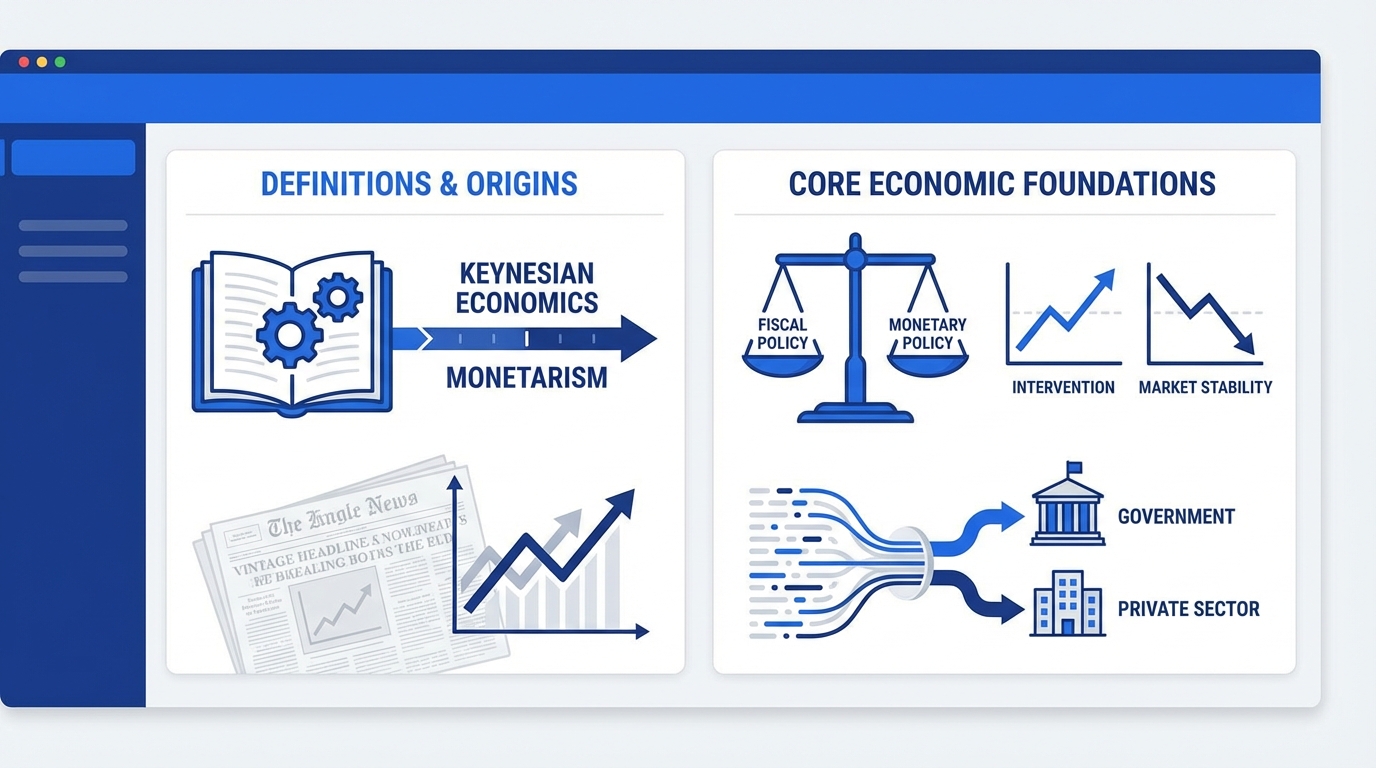

Definitions, Origins, and Core Economic Foundations

Macroeconomics is primarily influenced by two key schools of thought from the 20th century: Keynesian economics and Monetarism. These theories offer vastly different prescriptions for managing the economy, particularly concerning the necessity and utility of government intervention.

Both frameworks seek macroeconomic stability, low unemployment, and controlled inflation, but they differ significantly in their views on the stability of the private sector. This foundational conflict dictates their contrasting views on policy mechanisms.

This analysis provides a comprehensive comparative framework, tailored for advanced undergraduate study in Economics. It examines the theoretical origins, policy implications, historical context, and modern evolution of these two critical perspectives.

Understanding this core dichotomy is essential for interpreting current economic policy regarding inflation, unemployment, and long-term economic growth. Policy decisions from these models directly affect financial metrics and asset performance, including Stocks, Bonds, and ETFs.

Macroeconomic debates are crucial for both academic research and practical investing and personal finance strategies, whether in traditional banking or digital finance.

Keynesian Economics: Foundations and Principles

Keynesian economics began with John Maynard Keynes, particularly in his 1936 book, The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money. This school was established in response to the high unemployment during the Great Depression, arguing against the idea that markets self-correct automatically.

The core principle of Keynesianism is the principle of effective demand. Keynes argued that recessions are caused by insufficient aggregate demand (AD). He argued that prices and wages are “sticky,” meaning they don’t quickly decrease during economic downturns to restore full employment.

Keynesians use the income-expenditure model to show that an initial increase in government spending or investment can significantly boost overall Gross Domestic Product (GDP) through the multiplier effect. This framework justifies government intervention through discretionary fiscal policy to manage and stimulate aggregate demand during periods of low growth.

Monetarism: Foundations and Principles

Monetarism is linked to Milton Friedman, especially through his work A Monetary History of the United States, 1867 to 1960, co-authored with Anna Schwartz, which challenged Keynesian economics. Monetarists believe the private sector is inherently stable and self-regulating, provided that government interference is minimized.

Monetarism is based on the quantity theory of money, represented by the equation MV=PY, where M is the money supply, V is the velocity of money, P is the price level, and Y is real output. Monetarists believe that the velocity of money (V) remains stable over the long term, which implies that changes in the money supply (M) mainly influence nominal GDP (PY).

Monetarists argue that inflation is always and everywhere a monetary phenomenon, caused by the money supply growing faster than output. They stress the long-term neutrality of money, stating that monetary policy can influence output in the short run, but its only lasting impact is on the price level.

This school introduced the natural rate of unemployment (NRU), arguing that trying to lower unemployment below this level will only lead to higher inflation, not lasting job growth.

Foundational Views and Core Principles

Keynesian Economics: Foundations in Aggregate Demand

Keynesian economics is rooted in the seminal work of John Maynard Keynes, specifically his 1936 publication, The General Theory of Employment, Interest, and Money. This framework arose in response to classical economic models’ failure to explain the prolonged stagnation of the Great Depression.

The core tenet of Keynesian theory centers on the concept of effective demand. Keynesians posit that the private economy is not inherently self-regulating, especially in the short run. Recessions are understood as periods where insufficient aggregate demand (AD) prevents the economy from reaching its full employment potential.

A crucial assumption is the presence of sticky wages and prices. Due to institutional factors such as labor contracts and administered pricing, wages and prices do not adjust rapidly downward during downturns. This rigidity prevents the economy from quickly self-correcting back to full capacity, justifying proactive government intervention.

The policy implication is the management of aggregate demand, often through discretionary fiscal policy. Key mechanisms include the multiplier effect, where changes in government spending or investment lead to proportionally larger shifts in national income, influencing overall market conditions for Stocks and Bonds.

Monetarist Economics: Emphasis on Monetary Stability

Monetarism is primarily associated with Milton Friedman and the Chicago School, gaining substantial academic and policy influence from the 1950s onward. Monetarists fundamentally believe in the inherent stability and efficiency of the private sector and assert that macroeconomic fluctuations are predominantly caused by erratic monetary policy.

The intellectual bedrock of Monetarism is the modern interpretation of the Quantity Theory of Money (QTM), summarized by the equation of exchange: MV=PY. Monetarists assume that the velocity of money (V) is stable or highly predictable, and that real output (Y) tends toward the natural rate in the long run.

Consequently, Monetarists argue that changes in the money supply (M) are the primary, direct determinant of the price level (P). They reject the Keynesian focus on sticky prices, maintaining that markets are generally flexible and clear efficiently over time.

This perspective leads to the famous dictum that inflation is “always and everywhere a monetary phenomenon,” resulting exclusively from an excessive growth rate in the money supply relative to output. Friedman’s extensive empirical analysis, including A Monetary History of the United States, 1867 to 1960 (co-authored with Anna Schwartz), provided compelling evidence that monetary factors drove major economic shifts, profoundly affecting Investing decisions and the Banking sector.

Contrasting Core Mechanisms and Assumptions

The divergence between the two schools stems from fundamental disagreements regarding core economic mechanisms, stability, and the role of money. These theoretical differences have profound implications for policy, influencing modern approaches to setting Mortgage Rates and CD Rates.

-

- Stability of the Economy: Keynesians view the economy as inherently unstable, prone to protracted periods of underemployment due to deficiencies in aggregate demand. Monetarists view the private sector as inherently stable, asserting that instability primarily arises from external shocks, particularly flawed government intervention or central bank errors.

- Price/Wage Flexibility: Keynesians emphasize sticky wages and prices, which justify short-run demand management. Monetarists emphasize price flexibility and the economy’s long-run tendency toward the natural rate of employment.

- Role of Money: For Keynesians, money primarily affects interest rates, which then influence investment and aggregate demand. For Monetarists, money supply growth directly affects nominal GDP and, in the long run, only the price level.

- Velocity of Money (V): Monetarists assume V is stable, making the link between M and P reliable. Keynesians often argue that V is highly variable and sensitive to interest rates and expectations, weakening the predictability of the Quantity Theory of Money.

Understanding these foundational contrasts is critical for analyzing modern financial instruments, including ETFs and complex Options and Derivatives, as their valuation is sensitive to expectations about inflation and economic stability.

The rise of social media platforms like LinkedIn, Facebook, and YouTube has further accelerated the dissemination of Economics and Personal Finance content, highlighting how these historical debates remain relevant to contemporary market analysis and Trading strategies.

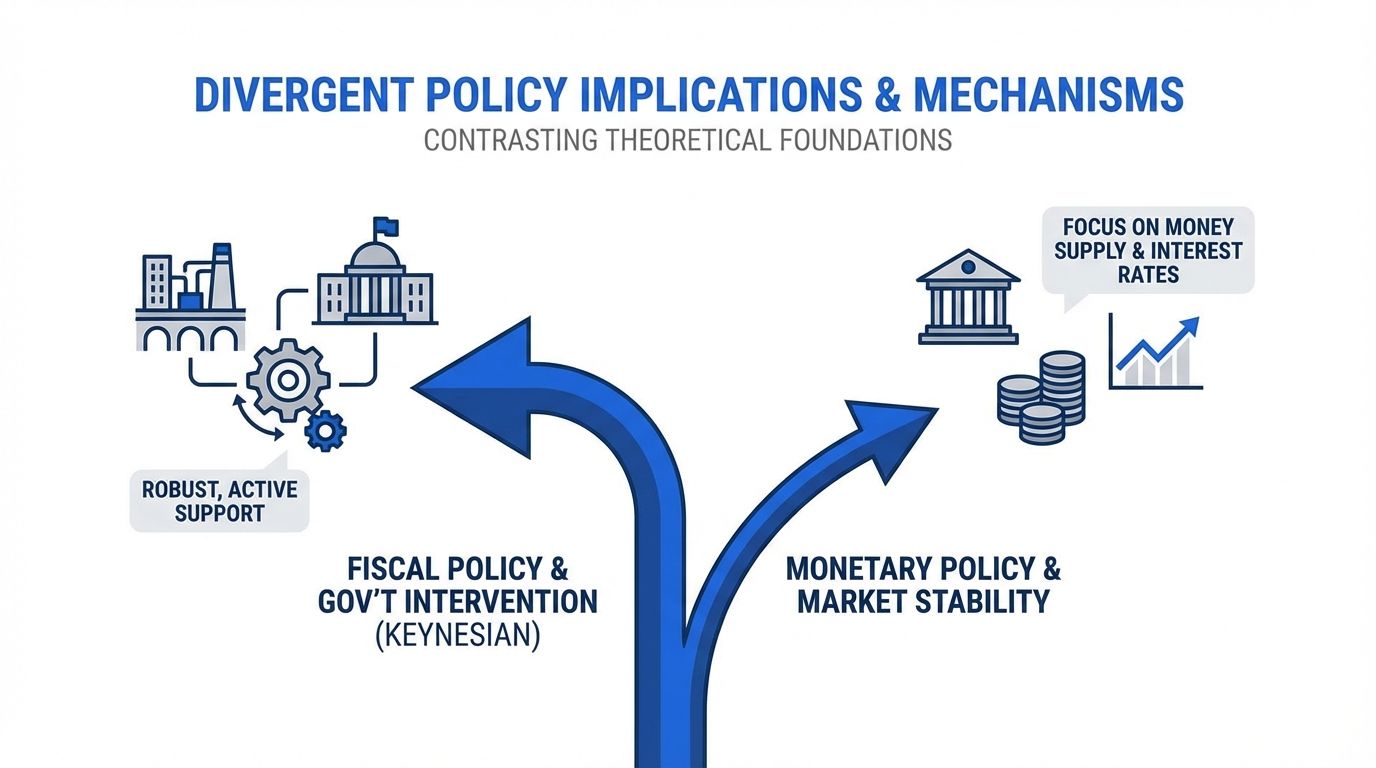

Divergent Policy Implications and Mechanisms

The contrasting theoretical foundations regarding market stability and the role of money lead to radically different recommendations concerning macroeconomic policy and the appropriate scope of government intervention. These differences manifest most clearly in the debate over fiscal versus monetary policy effectiveness.

Fiscal Policy and Government Intervention

Keynesian economics advocates for robust and active fiscal policy, particularly during protracted recessions or periods characterized by low aggregate demand. Proponents recommend strategic increases in government spending or targeted tax cuts designed to directly inject funds into the circular flow of income.

The rationale for this approach hinges on the multiplier effect, which posits that the overall stimulus to Gross Domestic Product (GDP) will be greater than the initial outlay. Deficit spending is viewed not as a liability during a downturn, but as a necessary counter-cyclical tool to restore full employment and encourage private sector investment.

Monetarists, conversely, exhibit profound skepticism regarding discretionary fiscal policy. They argue that government borrowing required to finance stimulus often leads to the phenomenon known as crowding out. Increased demand for loanable funds by the government drives up interest rates, thereby deterring private sector activity, such as business expansion and household purchasing of large assets like real estate or durable goods.

Furthermore, Monetarists contend that fiscal policy is inherently subject to significant operational lags and is often compromised by political motivations. They assert that the inherent stability of the private market economy requires minimal government intervention, preferring that resources be allocated through efficient market mechanisms rather than centralized planning. This focus on market efficiency often extends to the financial sector, influencing decisions related to Investing in Stocks and Bonds.

Transmission Mechanisms and Policy Lags

The effectiveness of any policy is heavily dependent on the speed and reliability of its transmission mechanism, the path through which policy changes affect real economic variables.

For Keynesians, the primary transmission mechanism for fiscal policy is direct: government spending immediately increases aggregate demand, which, via the multiplier, boosts income and consumption. Monetary policy transmission works through interest rates; lower central bank rates reduce the cost of borrowing for Banking institutions, theoretically stimulating investment and increasing asset prices for portfolios holding ETFs and other financial instruments.

Monetarists, however, emphasize the direct link between the money supply and aggregate spending. Their transmission mechanism is broader, asserting that changes in the money supply affect all assets, not just Bonds. An increase in the money supply leads to an excess of money balances, which households and firms attempt to reduce by increasing their spending on goods, services, and financial assets, including Stocks and Trading activities.

Both schools acknowledge the existence of policy lags, but their emphasis differs. Keynesians are often concerned with the recognition lag (identifying the recession) and the implementation lag (getting fiscal spending bills passed). Monetarists primarily focus on the impact lag, the often long and variable time it takes for monetary policy changes to affect inflation and output. Milton Friedman famously argued that these long and unpredictable lags render discretionary monetary policy destabilizing.

Monetary Policy Rules and Inflation Control

The schools fundamentally diverge on the management of the money supply. Keynesians historically viewed monetary policy as less potent than fiscal policy, especially during a severe downturn. This view stems from the concept of the liquidity trap, a situation where interest rates are near zero and further increases in the money supply are simply hoarded rather than borrowed or spent. In such scenarios, the ability of the central bank to influence investment, Mortgage Rates, or Personal Finance decisions is severely diminished.

Conversely, Monetarists regard monetary policy as the singular most powerful determinant of long-run economic outcomes, particularly inflation. They contend that “inflation is always and everywhere a monetary phenomenon.” However, they staunchly reject discretionary fine-tuning by the central bank, arguing that such actions introduce unnecessary volatility.

The Monetarist solution is a rules-based framework, most notably the k-percent rule proposed by Friedman. This rule dictates that the central bank should increase the money supply at a fixed, constant annual rate, ideally matching the long-run growth rate of real GDP. The predictability of this rule is intended to stabilize expectations, eliminate policy uncertainty, and ensure long-run price stability.

This rules-based approach contrasts sharply with the Keynesian preference for adjusting interest rate targets based on current economic data, often utilizing tools like automatic stabilizers rather than fixed rules to manage demand.

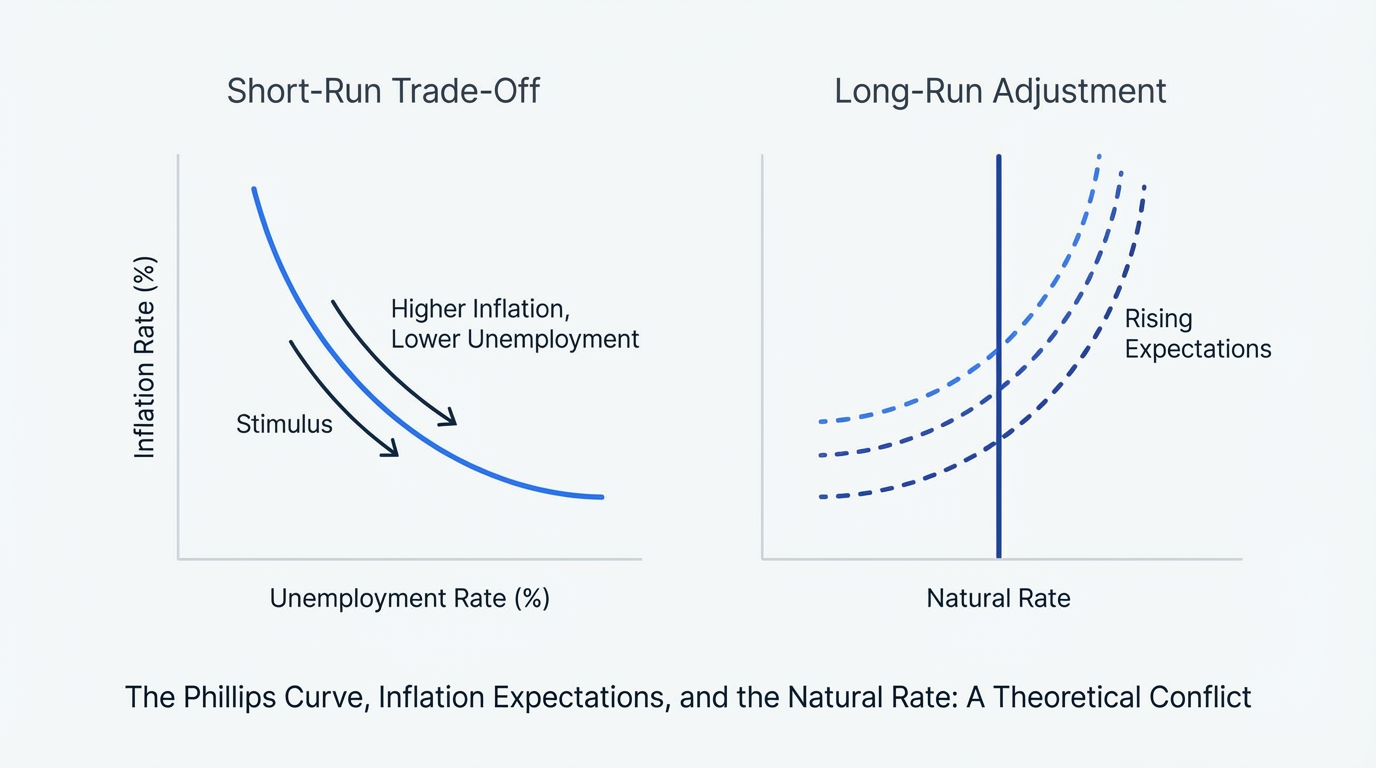

Contrasting Views on the Phillips Curve

The theoretical differences concerning the causes of inflation and unemployment are formalized in their differing interpretations of the Phillips Curve, which illustrates the relationship between these two variables.

Early Keynesian models embraced the traditional Phillips Curve, accepting a stable, exploitable short-run trade-off: policymakers could accept higher inflation in return for lower unemployment. This perspective justified expansionary demand management policies aimed at reducing joblessness.

Monetarists fundamentally challenged this view. Friedman introduced the concept of the long-run vertical Phillips Curve and the Natural Rate of Unemployment (NRU). Monetarists argue that while expansionary policy might temporarily reduce unemployment below the NRU in the short run (by surprising workers with unexpected inflation), in the long run, expectations adjust. Workers demand higher wages, increasing costs, and the economy returns to the NRU, but at a permanently higher rate of inflation.

Therefore, Monetarists conclude that there is no long-run trade-off between inflation and unemployment. Any attempt to use monetary or fiscal policy to keep unemployment below the NRU will only result in accelerating inflation, a core finding that heavily influenced modern central banking practices, including the establishment of inflation targets.

The primary policy divergence centers on the effectiveness of monetary versus fiscal tools. Keynesians prioritize fiscal action and discretionary demand management, viewing stable Banking and low interest rates as secondary during deep recessions. Monetarists prioritize stable, rules-based monetary control to manage inflation and maintain long-run stability, asserting that sound monetary policy is the prerequisite for healthy private sector Investing and sustainable economic growth.

The Phillips Curve, Inflation Expectations, and the Natural Rate

The debate over the relationship between inflation and unemployment, represented by the Phillips Curve, highlights a core theoretical conflict between the two schools.

Keynesians initially accepted the traditional short-run Phillips Curve. This model suggested a stable, exploitable trade-off where policymakers could stimulate aggregate demand to reduce unemployment by accepting marginally higher inflation.

This belief informed policy decisions throughout the 1960s, treating the inflation-unemployment relationship as a menu of choices for active demand management.

Monetarists, led by Milton Friedman and Edmund Phelps, fundamentally challenged this notion. They introduced the concept of the Natural Rate of Unemployment (NRU), also known as the Non-Accelerating Inflation Rate of Unemployment (NAIRU).

The Monetarist view posits that, in the long run, the Phillips Curve is vertical. This is because any attempt by policymakers to push unemployment below the NRU using expansionary policy will result only in accelerating inflation, as expectations adjust.

When policymakers fail to respect the NRU, the resultant instability, high inflation combined with policy uncertainty, can negatively influence the performance of financial assets like Stocks and Bonds, complicating Investing decisions.

The Monetarist perspective emphasizes that institutional factors, rather than aggregate demand management, determine the long-run unemployment rate. This theoretical insight proved crucial during the stagflation of the 1970s.

During this period, high inflation coincided with high unemployment. This empirical reality discredited the stable short-run Keynesian trade-off and shifted policy focus toward monetary rules and inflation control to stabilize the overall Economy and manage expectations regarding interest rates and CD Rates.

Historical Dominance and Real-World Applications

The Era of Fiscal Management (1930s to 1970s)

Following the devastation of the Great Depression, Keynesian principles became the standard framework for macroeconomic policy across developed nations. The success of the New Deal in the United States and the massive public works spending required for post-World War II reconstruction validated the utility of discretionary fiscal policy and deficit spending.

This period relied heavily on aggregate demand management to maintain near full employment. Policy decisions heavily influenced capital markets, driving significant Investing decisions based on anticipated government spending and Economy News.

The Stagflation Challenge and Monetary Control (1970s to 1980s)

The Keynesian framework encountered significant challenges during the 1970s, particularly with the phenomenon of stagflation, concurrent high inflation and economic stagnation. This crisis severely undermined the traditional short-run Phillips Curve trade-off, which Keynesians had largely accepted.

Monetarism, championed by Milton Friedman, provided a compelling alternative diagnosis. The school argued that excessive growth in the money supply, rather than structural issues, was the primary cause of persistent inflation.

This led to a global policy shift prioritizing monetary discipline. Central banks, notably the U.S. Federal Reserve under Paul Volcker, adopted strict monetary targeting rules. This shift dramatically impacted the Bonds market and required extensive coordination with the Banking sector to stabilize prices and control inflation expectations.

Contemporary Application and Policy Blending

Modern policy responses often reflect a pragmatic synthesis of both schools. The 2008 Global Financial Crisis and the subsequent economic downturns, including the COVID-19 pandemic, necessitated swift and massive government action.

Fiscal policy utilized large-scale stimulus packages, reflecting Keynesian demand management. Simultaneously, central banks executed unprecedented quantitative easing (QE), a massive expansion of the money supply, which aligns closely with the concerns of monetary policy regarding liquidity and interest rates.

These actions fundamentally altered the landscape for Stocks and Exchange-Traded Funds (ETFs). The injection of liquidity into the system, combined with low interest rates, has driven considerable debate among analysts regarding the long-term inflationary risks versus the immediate need for economic stabilization and recovery in global Markets News. Decisions regarding Trading strategies are now intrinsically linked to central bank communications and fiscal stimulus announcements.

Synthesis and Modern Evolution

The strict intellectual dichotomy that once separated Keynesianism and Monetarism is largely obsolete in contemporary macroeconomics. Modern policy frameworks and theoretical models incorporate foundational elements from both schools, resulting in sophisticated hybrid approaches.

This evolution was necessary to address the complex economic challenges of the late 20th and early 21st centuries, particularly stagflation and global financial crises.

The Rise of Microfoundations and Hybrid Models

A significant impetus for the synthesis was the emergence of the New Classical school in the 1970s. This school, heavily influenced by Monetarist rigor, introduced the concepts of rational expectations and efficient markets, fundamentally challenging the assumption that policymakers could systematically exploit short-run trade-offs.

In response, New Keynesianism developed. This framework retained core Keynesian beliefs regarding market imperfections, such as sticky wages, sticky prices, and monopolistic competition. Crucially, however, New Keynesian models integrated rational expectations and rigorous microfoundations, addressing the New Classical critique head-on.

These models, including Dynamic Stochastic General Equilibrium (DSGE) models, now form the theoretical backbone for sophisticated analysis used in global Banking and by major financial institutions involved in Investing and Trading.

Modern Policy Frameworks: Blending the Schools

Contemporary central banking exemplifies the practical blending of these two traditions. The primary operational mandate of many central banks, including the Federal Reserve, is inflation targeting, a concept deeply rooted in the Monetarist conviction that long-run price stability is paramount for economic health and confidence in capital markets, including those for Stocks and Bonds.

However, the tools used to achieve this stability are distinctly Keynesian. Central banks utilize flexible, discretionary interest rate adjustments and forward guidance, focusing on the price of money rather than a strict money supply rule. Furthermore, unconventional tools like Quantitative Easing (QE) involve active intervention in the Markets News cycle and the purchase of long-term government Bonds and other assets, reflecting a highly discretionary Keynesian approach to managing aggregate demand.

Regarding fiscal policy, the Keynesian legacy remains dominant during deep recessions. Governments routinely deploy large-scale fiscal stimulus packages, acknowledging the short-run effectiveness of government spending in increasing aggregate demand and mitigating unemployment, particularly when interest rates are near zero (the liquidity trap).

Conversely, the Monetarist influence ensures that policymakers are acutely aware of the long-term inflationary risks associated with excessive money supply growth and large government deficits, which can influence Mortgage Rates and the viability of Savings Accounts.

The Lasting Legacy in Finance and Personal Finance

Both schools provide essential analytical lenses for understanding the Economy News and formulating effective policy. Monetarism permanently shifted the focus of central banks toward the control of inflation and the importance of credible, rules-based policy communication.

Keynesianism provided the framework for utilizing fiscal policy and automatic stabilizers to address cyclical unemployment and maintain stability in the short run. This stability is critical for fostering confidence in capital markets, supporting the growth of Exchange-Traded Funds (ETFs) and overall Personal Finance planning.

Discussions regarding policy effectiveness, debt sustainability, and the optimal timing of interventions are regularly shared across professional platforms such as LinkedIn and financial news outlets like Investopedia. These forums highlight that policy decisions today are rarely purely Keynesian or purely Monetarist, but rather a nuanced assessment of current economic conditions, public expectations, and the relative potency of fiscal versus monetary tools.

Ultimately, modern macroeconomics recognizes that the money supply is critical (Monetarist view), but its relationship with inflation and output is mediated by market imperfections and expectations (New Keynesian view).

Critical Synthesis and Core Theoretical Contrasts

While modern economic policy often employs hybrid approaches, the core theoretical divergences between Keynesianism and Monetarism remain crucial for interpreting current economic data and policy decisions.

These foundational differences influence how policymakers respond to macroeconomic instability, affecting outcomes across Investing, Personal Finance, and the markets for Stocks and Bonds.

Understanding these contrasting views on monetary velocity and government intervention is essential for analyzing interest rate movements, including fluctuating Mortgage Rates and returns on Certificates of Deposit (CDs).

The table below provides a detailed summary of the fundamental contrasting positions of these two schools across dimensions critical to policy formulation and market stability.

| Dimension | Keynesian Economics | Monetarist Economics |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Policy Tool | Discretionary Fiscal Policy (Government Spending, Taxation) | Rules-Based Monetary Policy (Money Supply Control) |

| View on Self-Correction | Slow and unreliable; markets can be stuck below full employment due to sticky wages and prices. | Rapid and reliable; markets inherently self-correct to the natural rate of output and employment. |

| Cause of Recession | Insufficient Aggregate Demand (AD), resulting from low confidence or inadequate investment. | Monetary contraction or instability in the money supply (M), leading to nominal income fluctuations. |

| Cause of Inflation | Excessive AD, pushing output beyond potential capacity (demand-pull inflation). | Excessive growth of the money supply (M) relative to output growth. |

| Stability of Velocity (V) | Unstable and unpredictable, making the Quantity Theory of Money unreliable for policy Trading. | Stable and predictable in the long run, validating the direct link between M and P. |

| View on Government Deficits | Necessary during severe recessions to stimulate demand and utilize idle resources. | Detrimental; leads to “crowding out” of private investment and higher future taxes. |

Key Takeaways on Policy Implementation

The academic debate between these schools has yielded practical policy lessons that guide modern Banking and central authority actions.

Modern macroeconomic policy, often termed New Synthesis, acknowledges the short-run relevance of Keynesian demand management but mandates the long-run inflation control prioritized by Monetarism.

-

- Monetary Focus: Monetarism established the principle that central banks must maintain price stability as their primary long-run objective, leading to widespread adoption of inflation targeting strategies globally.

- Fiscal Focus: Keynesian theory justifies the use of automatic stabilizers and targeted fiscal stimulus during deep recessions, especially when interest rates are near zero and monetary policy is constrained.

- Expectations: The Monetarist emphasis on rational expectations and the Natural Rate Hypothesis forced policymakers to recognize that short-run trade-offs between inflation and unemployment are temporary. This impacts investment strategies involving Exchange-Traded Funds (ETFs) and other financial instruments.

- Market Stability: While Keynesians highlight market failures requiring intervention, Monetarists stress the importance of rules-based policy to prevent government actions from becoming an independent source of economic instability. This perspective informs regulatory approaches across various financial platforms, including those discussed on sites like Investopedia or professional forums on LinkedIn.

Key Takeaways and Modern Synthesis

The academic debate between Keynesianism and Monetarism has profoundly shaped macroeconomic theory and policy since the mid-20th century. Understanding these differences is essential for analyzing modern economic challenges, such as determining the correct governmental response to rising inflation or managing volatility across global Trading markets.

While contemporary policy frameworks often blend these schools, their core theoretical divergences remain critical for interpreting Economy News and making sound Investing decisions.

Fundamental Theoretical Contrasts

-

-

Time Horizon Focus: Keynesian theory excels in explaining short-run fluctuations and managing recessions due to its emphasis on sticky prices and effective demand management. Monetarism provides a superior framework for long-run analysis, particularly regarding the determination of the price level and the inherent dangers of sustained high inflation.

-

Primary Policy Tool: Keynesians prioritize discretionary fiscal policy (government spending and taxation) to directly influence aggregate demand. Monetarists advocate for monetary policy, specifically targeting the stable growth of the money supply, believing fiscal tools are often ineffective or counterproductive due to crowding out.

-

View on Stability: Keynesian thought assumes the private sector is inherently unstable and prone to long periods of underemployment equilibrium, necessitating government intervention. Monetarist thought assumes the private sector is inherently stable and self-correcting, viewing instability as primarily a result of erratic government or central bank policy.

-

Policy Implications and Market Impact

The differing views on policy efficacy directly influence policy responses to crises, which in turn affects returns on assets like Stocks and Bonds.

-

-

Policy Efficacy and Lags: The Keynesian approach advocates for activism, believing policy can effectively stabilize the economy. The Monetarist approach favors policy restraint and rules, viewing discretionary intervention as destabilizing due to significant policy lags (recognition, implementation, and impact lags) that can exacerbate economic cycles.

-

Inflation Management: Keynesians typically view inflation as a consequence of excessive aggregate demand, often controllable through fiscal means. Monetarists maintain that inflation is fundamentally a monetary phenomenon, always and everywhere caused by the money supply growing faster than output. This insight forms the basis for inflation targeting used by modern central Banking institutions.

-

Financial Market Stability: Monetarist adherence to rules-based growth provides predictability, which is often favored by capital markets. Conversely, Keynesian discretionary stimulus during deep recessions can stabilize employment and consumer confidence, indirectly benefiting investment in assets such as ETFs and stabilizing Personal Finance outlooks.

-

Enduring Legacy in Contemporary Economics

The evolution of macroeconomic thought has not eliminated these schools, but rather incorporated their strongest components into hybrid models, such as New Keynesianism, which utilizes microfoundations and rational expectations.

-

-

Keynesian Legacy: Concepts such as automatic stabilizers, the multiplier effect, and the critical role of aggregate demand management remain central to modern recession management and fiscal stimulus debates, including post-2008 quantitative easing programs.

-

Monetarist Legacy: Monetarist principles, particularly the focus on monetary aggregates, the long-run vertical Phillips Curve, and the critical importance of price stability, form the bedrock of modern central bank independence. Central bank mandates to control inflation directly determine the interest rate environment, influencing products like CD Rates and Mortgage Rates.

-

Synthesis: Modern policymakers largely accept the Keynesian view for short-run stabilization during deep downturns but adhere to the Monetarist principle that money is neutral in the long run, making price stability the ultimate objective for sustained economic growth.

-

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the primary difference between Keynesian and Monetarist views on inflation?

Keynesians generally interpret inflation as a demand-pull phenomenon. It arises when aggregate demand exceeds the economy’s productive capacity, typically occurring near full employment. This perspective often informs analysis reported in Economy News regarding overheating markets.

Monetarists strictly adhere to the view that inflation is exclusively a monetary phenomenon. It results when the growth rate of the money supply consistently surpasses the growth rate of real output. This imbalance directly impacts the value of currency used in Trading and Investing activities.

How do these schools view the role of expectations in the economy?

Traditional Keynesian models focused primarily on current income and short-run price rigidities, giving less weight to explicit forward-looking expectations.

Monetarism, especially when integrated with the Rational Expectations hypothesis, views expectations as central to economic outcomes. Agents, including those making decisions about Stocks, Bonds, and other financial products, anticipate future policy actions.

This anticipation reduces the efficacy of discretionary policy, as market participants anticipate and neutralize its intended effects. This concept is vital for professionals analyzing market movements on platforms such as LinkedIn.

Which school of thought is more relevant to current central bank policies, such as Quantitative Easing (QE)?

Modern central banking, particularly concerning Quantitative Easing (QE) and inflation targeting, operates as a synthesis of both schools.

The explicit commitment to price stability and controlling inflation aligns with the core Monetarist priority. However, the use of highly discretionary, interest-rate focused tools reflects a Keynesian reliance on active management.

QE is fundamentally a monetary tool used by central Banking authorities to manage liquidity, directly affecting yields on Bonds and the valuation of Exchange-Traded Funds (ETFs). Its operation often requires parallel fiscal stimulus, demonstrating the necessary blend required to stabilize the Markets News and protect Personal Finance during severe economic downturns.

The use of complex instruments like Options and Derivatives further underscores the need for blended policy approaches in contemporary financial markets.